All of a sudden, things start to go badly. Support tickets begin to flood in with the same complaints - the app stops working. The engineers start to investigate in their own homes. The production app is on fire, and we are all remote.

Product incidents are stress-inducing. Every minute counts. A product incident when everyone works remotely is even more challenging. Incident management with a remote engineering team is a complex problem; this blog post attempts to provide some simple guidelines to follow.

what bad incident response looks like

Imagine a production outage happened with the following scenario:

- the outage is raised by customers first, not the engineering team

- the engineering team investigate the outage in silos

- the company does not have a common understanding of what and who is working on the outage

- the customers were left hanging without answers, and frustrated

The scenarios above paint a bleak picture. Such outage and respondence to outage damage customer trust and tarnish team morale. Unfortunately, these scenarios happen way too often at startups with small engineering team and fragile infrastructure. To add another layer of complication, having an all-remote engineering team means more required synchronization between individuals online.

So how can we do better? In order to do better, we first need to understand what makes production incidents difficult, and then apply guidelines to address them.

what makes production incidents hard to respond remotely

- production incidents requires fast response. When an incident happens, the most ideal is to identify the root cause and fix it as soon as possible.

- production incidents are unexpected and stress-inducing. Incidents are by nature not intentional, and thus the engineering team starts to tackle incidents with lots of unknowns. When we face unknowns with a ticking clock, it produces stress.

- direct communication is harder without being physically together. It gets harder to synchronize information with an all-remote team and have a single source of truth.

Some guidelines start to emerge given the constraints listed above.

guidelines to better incident respondence

detect problems before customers

Detect problems early, even better, fix the issue before it has a major customer impact. This can be done if and only if there’s a sufficient alerting and monitoring system. Great alerting and monitoring result from a good engineering culture, in that observability, is part of the development lifecycle. How to build such a culture is a topic of a whole blogpost along.

virtual command center

Create a virtual command center, broadcast details of the virtual command center to the company right away. Criteria of a solid virtual command center include but not limited to:

- A virtual conference room link that people can join

- A person in charge of the command center (declare at the start of the command center) - an incident commander

- Communication protocol in the command center (e.g., what to ask, what to share, how to act, etc.)

Condition, Actions, Needs (CAN) report

The concept of CAN report comes from progress reporting on the firegroud with firemen. This article further explain why this report is crucial:

Progress reporting on the fireground during all phases of operations relays vital information between the Incident Commander (IC) and companies operating at the incident. Incident action plans are driven by the completion of tactical objectives. Conversely, If an objective cannot be completed, the IC needs to be advised so that the safety of crews operating can be evaluated and the tactical and strategic plan modified.

An easy way to answer or transmit a progress report is the CAN report. The C A N report stands for Conditions, Actions, Needs. By using this order model, the person giving the report easily identifies how well they are doing, the conditions they are facing, and any support or resource needs that they have.

An example CAN report template can be found here.

modeled communication

Given a virtual command center is established, how can we act together? One inspiration comes from how Slack handles production incident. Specifically:

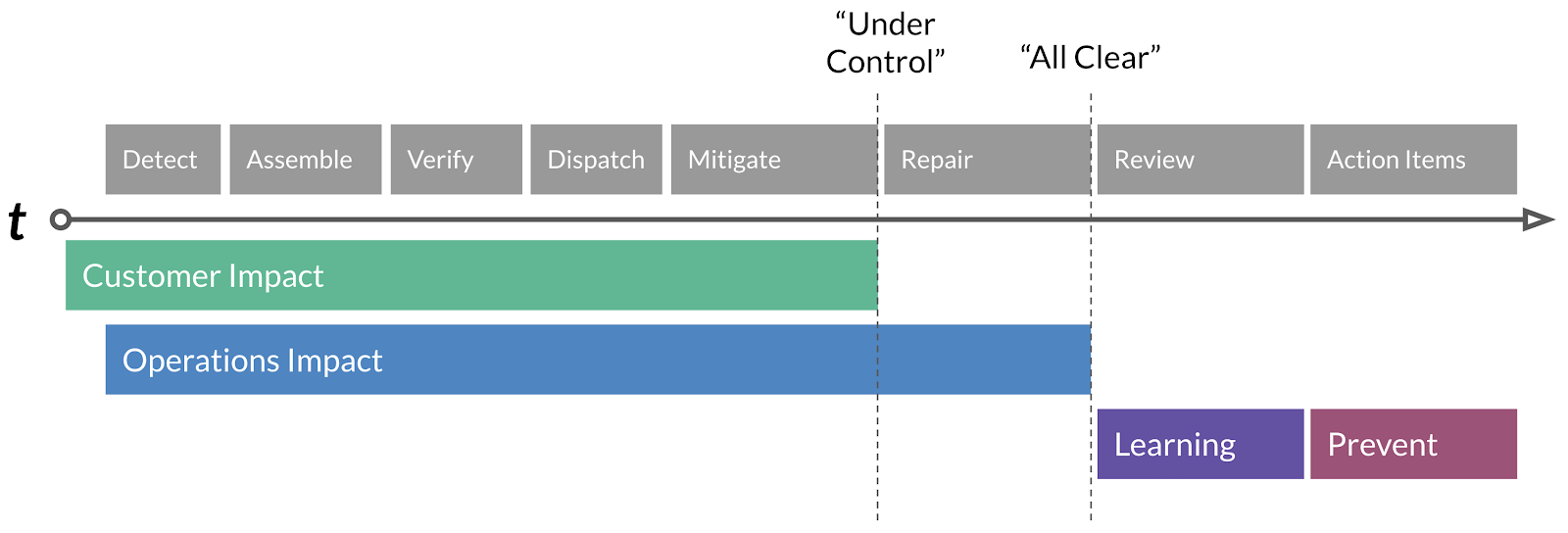

The timeline of an incident is composed of four distinct stages, Customer Impact, Operations Impact, Learning & Prevention. Within these stages, there are distinct operations that lead to the final resolution of an incident, which we’ll briefly summarize.

Detect: Detection of a regression or customer impact via, ideally, SLO failure, automated alerts driven by metrics, or less ideally, customer reports.

Assemble: The Subject Matter Expert (SME) who gets the initial Detect page will invoke the Assemble process and alert the Incident Commander on-call.

Verify: Incident Commander discusses with SME on initial scope of the impact as well as severity. Our first Conditions, Actions and Needs (CAN) reports can begin.

Dispatch: Incident Commander, based on the CAN report, will page additional SME’s as needed.

Mitigate: A diagnosis is presented, and a mitigation action is proposed & executed.

Repair: Typically, mitigations are temporary — an analogy would be duct-taping a leak. The repair action is a long term fix if needed.

Review: The Incident Review process kicks off and we review the incident and extract lessons and action items from it.

Action Items: We complete action items based on priority within defined SLA’s to further enhance prevention of the incident recurring.

Nearly every well-run incident can fit into the model above.

how to communicate to customers during an incident

While the incident is happening, it’s crucial to keep customers in the loop. Information should be shared with customers when an incident enters a new stage. It is the responsibility of an incident commander to communicate when an incident enters a new stage. It is the Customer Success team’s responsibility to communicate out to customers when the stage is changed.

conclusion

Running production incidents well takes a clear framework and practice with that framework. A well-run incident rebuilds customer confidence and boosts team morale, and it’s one key skill for engineering leaders to master.